The little-known story of Florida's first school to become integrated

Family on the front lines of desegregating Florida’s schools, beaches, and pools

Craig Patrick reports

RIVERVIEW, Fla. - America’s civil rights movement took off in the early 1960s with sit-ins in North Carolina, the Freedom Riders, student protests, and public bus boycotts led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

When Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat in Montgomery, Alabama, it motivated similar protests in Florida. Reverend C.K. Steele and FAMU students boycotted the Tallahassee bus system. Patricia Stephens Due helped lead Florida's sit-ins. And a nurse from Jacksonville named Irvena Prymus integrated Florida schools in a story seldom told.

Irvena Prymus, Florida civil rights pioneer

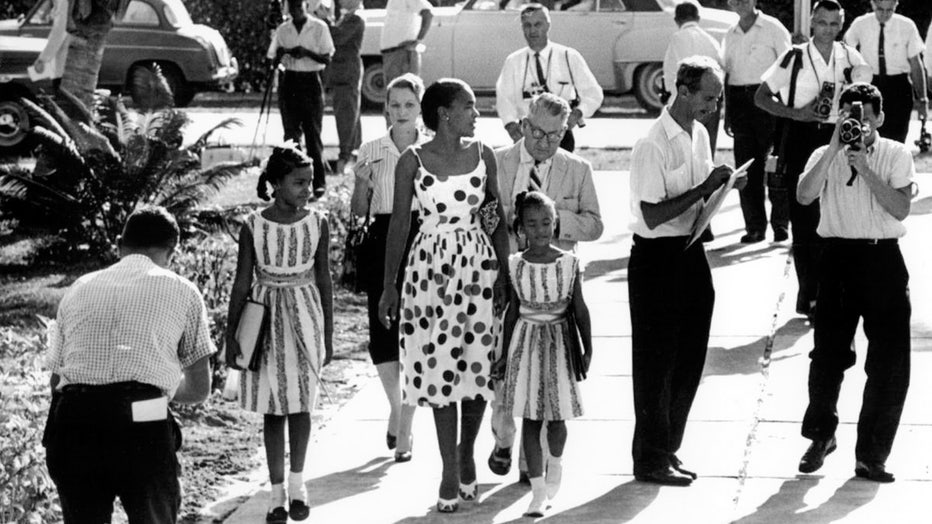

Irvena's daughters, 9-year-old Jan and 7-year-old Irene, were Florida's trailblazers when their mom enrolled them at Orchard Villa School in South Florida.

Irvena’s daughter Irene Glover Calhoun, who now lives in Riverview, shared her stories with FOX 13 of how it all played out back in 1959. She said she just remembers feeling excited to go to school for the first day. As a 7-year-old, she did not understand why journalists were following her, or the impact of her mother’s decision to enroll her in a segregated school.

The rise of the fall of segregation

Before Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s messages became widely-held beliefs, those who wished to suppress the rights of African Americans employed every means necessary to maintain segregation.

Irvena was Native American. When she enrolled her two daughters, she did not tell the school their father was black. School administrators did not realize they were enrolling African American students -- until word spread on the first day of school and reporters showed up.

Irvena Prymus escorts her daughters into the Orchard Villa School on Sept. 8, 1959. Photo via the State Archives of Florida.

"They said, ‘You can't do it.’ She said, ‘Oh, we’ll see about that,’” recalled Irene. “She was making that first step. First step for integration. I guess she was excited too. But my father didn’t like it. Not at all. My father was a mortician and he was afraid…to see us on that table someday. My mother still stepped out there, no matter what. Strong cookie!”

Local officials responded by filing a court challenge to kick the girls out, and the principal sent them home on their first day.

"[My mother] said, ‘You might stop me today, but I’ll be back tomorrow.’”

A couple of weeks later, she won in court and the girls were back.

"We had no problems with the other students. They were nice."

Irene Glover Calhoun smiles as she recalls her mother's role in the civil rights movement.

Sadly, before she knew it, the other students were gone.

"I think not long after that, the school was entirely African American. All the white families moved out of the neighborhood,” Irene continued. “But this was the first step, and I think it straightened out after a few years."

Meanwhile, her mother continued to take down Jim Crowe laws across the state.

"So what my mother did, she sued Dade County Parks and Recreation and she won, so we started going to the pool," Irene said. "She did the same thing with the movie theatre, and the beaches. She also fought for that and she won."

Turning point: Dr. King’s plan for Alabama

Stories from the family who harbored Dr. King while protests raged in Birmingham, Alabama, his secretary who was tasked with getting a message to the public, and thousands who filled the streets to demand justice.

She filed the lawsuits that crushed segregation ordinances through much of Florida. But she disliked attention and avoided exposure, and never gave an interview. Her legacy is therefore largely lost to history.

She passed 10 years ago, just as racial tensions began to flare in our country yet again.

"That's the only reason I did this interview with you,” Irene added. “Because I’m so proud of her and I think people should know.”

Florida's Path to Equality, full show

As the nation honors the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, we're taking a closer look at Dr. King's connections to Florida. FOX 13’s Craig Patrick spent the past five months meeting the people who knew him well and tracking the path to equality. Here’s the full show as it aired on January 20, 2020.