In scientific first, Florida Aquarium cross-breeds corals for stronger disease resistance

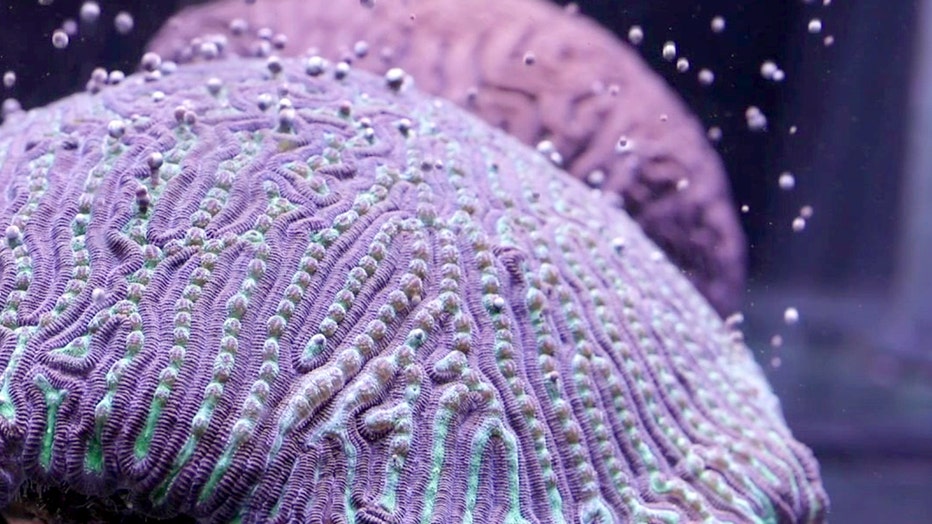

TAMPA, Fla. - The Florida Aquarium has some exciting news that's three years in the making. Scientists successfully cross-bred grooved brain corals from two different locations that were rescued from a disease outbreak.

It's a first-of-its-kind achievement that could have a major impact on saving Florida's depleted coral reefs.

You don't have to be a scientist to care about this. Reefs are crucial, especially in Florida. They protect our coasts and maintain the ecosystem underwater, which has a ripple effect on the state's fishing and tourism industries.

Keri O'Neil, the senior coral scientist with The Florida Aquarium, says these particular corals may look just like brains, but it's going to take a lot of human brainpower to save them.

"How do we build a stronger population?" O'Neil asked. "Florida's corals are facing a lot of threats right now."

(Florida Aquarium)

The threats range from pollution to rising seawater temperatures to disease.

Since appearing in 2014, Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease has devastated Florida's reefs. In 2018, FWC and NOAA began removing grooved brain corals before they could be impacted and distributing them to public aquariums in the U.S. like The Florida Aquarium.

PREVIOUS: Corals rescued from disease spreading along Florida's southeastern coast

"How do we selectively breed corals that are resistant to some of these things?" O'Neil wondered.

Last month, they teamed up with the University of Miami to try something that's never been done: breed brain coral from a lab with wild coral, combining frozen sperm with fresh eggs.

(Florida Aquarium)

"We used a technique called cryopreservation to do that, essentially freezing that sperm so it's good indefinitely until it's spawned," O'Neil explained.

May 7, scientists from both coasts met in the middle at a fast-food parking lot in Naples. The Florida Aquarium traded its vials of sperm from rescue coral for UM's sperm taken from wild corals spawned in Key Largo.

They rushed back to the labs and within hours, the corals were spawning.

"They just come up in this perfect line," O'Neil said, describing the sight. "It just takes my breath away literally every single time I see it."

Their mission was a success and a huge step toward increasing genetic diversity and resilience in the Florida Reef Tract.

PREVIOUS: Florida Aquarium helps successfully transplant, grow coral in the wild

"By crossing these corals that have never been exposed to the disease with those that survived the disease, we hope that these offspring are actually a stronger population of corals than one or the other on its own," O'Neil said.

This was just the first step. The long-term goal is to eventually re-introduce these offspring with increased disease resistance into Florida's reefs.