'One common dust:' Historic Tampa love story echoes through the centuries

TAMPA, Fla. - At most cemeteries, it’s the loved ones who come by and pay their respects. But at Oaklawn Cemetery, it’s the strangers who pay a visit to a couple they never knew.

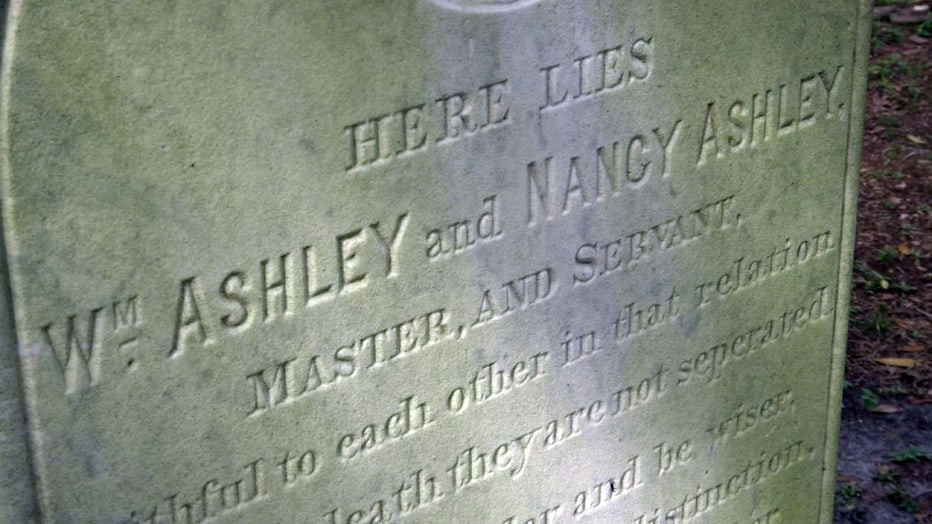

The time was one where masters and slaves existed, and that’s what William Ashley and Nancy were to one another. But the words on their headstone explain a bond much deeper.

The epitaph reads:

Here lies

Wm. Ashley and Nancy Ashley,

Master, and Servant,

Faithful to each other in that relation

in life, in death they are not seperated.

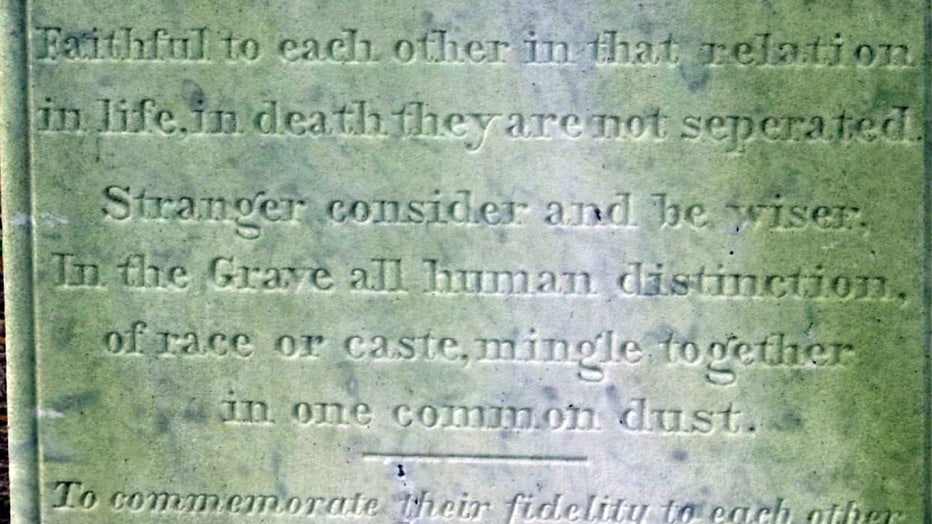

Stranger consider and be wiser,

In the Grave all human distinction,

of race or caste, mingle together

In one common dust.

To commemorate their fidelity to each other

this stone was erected by their Executor.

John Jackson, 1873.

Created in 1850, Oaklawn Cemetery is the final resting place for many of Tampa's founding fathers and their families.

University of South Florida librarian Drew Smith specializes in genealogy. He says the first glimpse of William and Nancy’s relationship comes before the Civil War.

"We know that Ashley created a will in 1857, where he wanted to leave all of his property to the enslaved woman, and he names her in the will," he said.

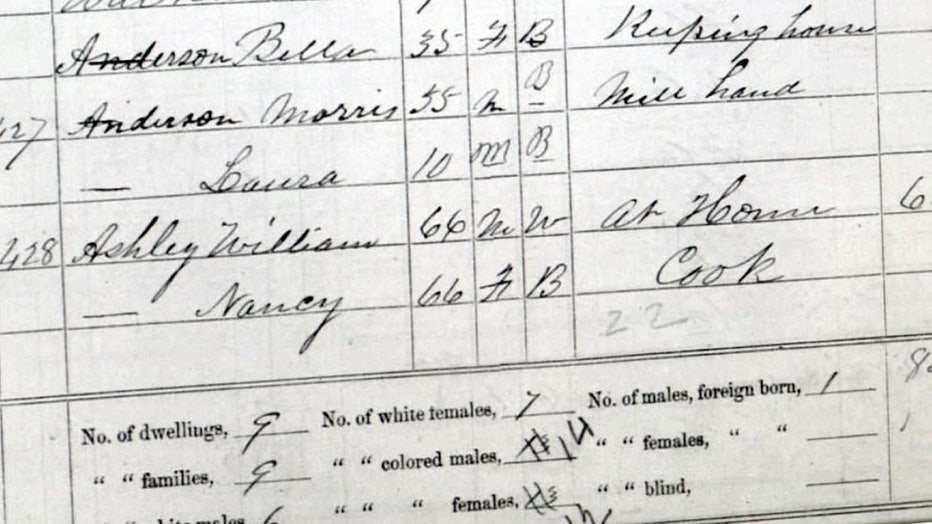

A slave schedule from 1850 shows William had a female slave who was his age. But it wasn’t until census records after the Civil War that we learn her name.

"Here lies Wm. Ashley and Nancy Ashley"

“We get to see them enumerated with all other residents of the United States," Smith continued. "So we see William Ashley, age 66, but also in the same household as Nancy. She’s listed as the same age, about 66, female, black, listed as ‘cook’ by occupation. We also know she continued to be in his household after the Civil War, after she’s emancipated, and we see that she’s actually living with him, under the name of Nancy Ashley, as his cook."

Smith explains that for Nancy, living as a free woman in a post-war South would have put her in a difficult place here in Tampa.

"She would have been a free person of color, but living in a society like Tampa that still had enslaved persons, and really nothing in the way of legal protection so that someone could have tried to take advantage of her and try to re-enslave her," Smith explained. "But I think once she had his resources, she could go somewhere else if she chose to."

Census records show William Ashley living with Nancy, officially listed as his cook.

But Nancy stayed – until her death in 1873.

Tampa’s first city clerk, William Ashley had a friend in John Jackson, a former Tampa mayor. Jackson became the executor of William and Nancy’s estate.

"After William is buried and Nancy dies and is buried, Jackson ensures they are buried together," Smith said.

“Now think about the time. This would not have been a time that would have been accepting of a white person and a black person being buried together. There was still a lot of efforts for segregation and discrimination, and this would normally have not been able to do. But Jackson made sure it happened. And he made sure there was an epitaph that kind of described that special relationship that William and Nancy had."

The epitaph's final line still resonates today.

And it's the final line, that Smith said, transcends time:

Stranger consider and be wiser,

In the Grave all human distinction,

of race or caste, mingle together

In one common dust.

"We are the stranger," Smith offered. "We are the person who doesn’t know this couple. We are not familiar with their story until we come upon their tombstone. And we look at it, and it speaks to us in saying, once you’re dead, all of these distinctions we make between human beings – between lower income, higher income, between white and black or whatever – none of those really matter anymore."

One of those strangers was Mike Fowler-Crews, who married his partner, Steve, at the cemetery in 2017.

He believes the Ashleys were trailblazers for their time.

Mike and Steve tied the knot at the Ashleys' headstone.

"We were just inspired,” he said. “They were kind of going through the same thing that we were going through about 10 years ago, because we would not have been allowed to marry. We really felt that connection with them."

It’s a connection carried on through these words, nearly 150 years later.