Largo residents to vote on whether city can sell 87-acre land for sports complex plans, not all are on board

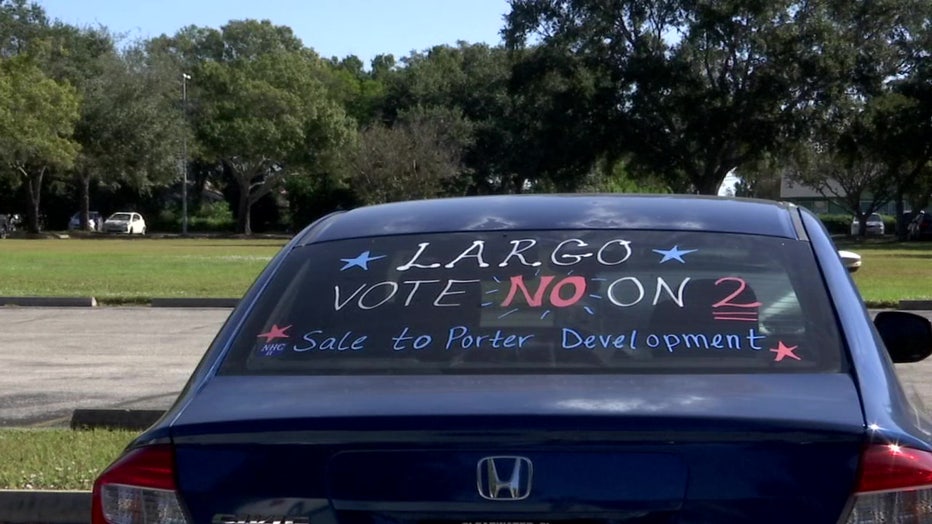

LARGO, Fla. - A huge sports complex could be coming to Largo. Residents will vote Tuesday on whether the city can sell the 87 acres of land to the developer of the project, Porter Development.

The site near Highland Avenue and East Bay Drive used to be a landfill.

"I thought it was a great opportunity to clean something up, create something awesome for the city and impact as few people as possible," Les Porter, the president of Porter Development, said.

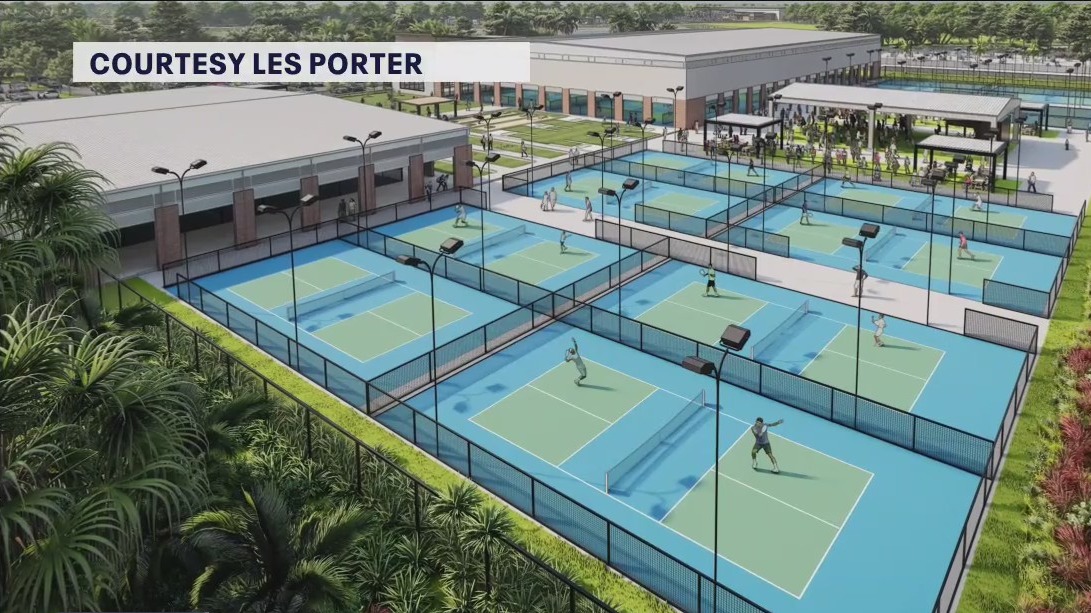

Porter said the space would include 40 pickleball courts, 16 volleyball courts and a lagoon for paddleboarding and kayaking, among other amenities. He also said the complex would be booked on weekends, and would be youth sports oriented.

Over the summer, Largo city commissioners voted to put the property on the ballot, asking voters if the city can sell the site to the developer. At the time, commissioners voted 4-2 to add the referendum to the ballot despite push back from residents.

RELATED: Largo residents push back on sports complex plans over traffic congestion concerns

Largo resident Megan Jetter, who lives about 200 yards from the site, some residents in her neighborhood put together a group to fight back against the referendum.

"This particular project is not necessarily bad in theory," Jetter said. "The location is an absolute no-go as far as it being landlocked, the traffic issues that it would cause, because it’s in such a small part of Largo."

Porter said a local consultant did a traffic study that the city reviewed. He said from an operational standpoint, it wouldn't impact the service level of roadways. Porter said they’ll continue to sit down and talk with the city’s engineering department to talk about ways to mitigate traffic, if the referendum is passed.

Jetter said she and her neighbors also have environmental concerns. The site sits right next to the Largo Nature Preserve.

READ: St. Pete voters to decide on Dali Museum expansion referendum

Porter said he and his team have done a preliminary environmental study which they submitted to the city and to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. He said they have an environmental engineer on staff, and plan to do a more in-depth study, but can’t do that until the city has the right to sell the property.

Porter said they also don’t plan to touch the trees on the property, and are exploring options when it comes to revitalizing the wetlands on the property.

He said he also hired a sports consulting management team that did an economic impact study. It predicted the project will bring in $16 million in annual economic impact, and 700,000 people each year. Jetter, though, said she and her neighbors don’t want the extra people.

"Largo is not meant to be a tourist destination," Jetter said. "Most of us I think live here, because it’s not a tourist destination. We’re close enough to the beaches to be able to enjoy them, but we still have a little bit of a smaller city feel here even with all of the development."

According to a spokesperson for the City of Largo, the property is not closed to the public right now, but it is not considered part of Largo Central Park or the Nature Preserve. The only current use is by the Largo Flying Club.

MORE: Florida voter survey: Rubio holds 6-point lead over Demings; DeSantis expands lead to 10 points

Porter said he met with the flying club and with neighbors in the plan’s early stages. He’s hoping the club can move to the former Toytown landfill in St. Petersburg.

The city spokesperson said they received an unsolicited proposal from Porter several months ago. The property wasn’t a proposed city project, and the city didn’t have any plans to use the land, she said. Porter and his team have since met with city officials several times, she said.

If voters approve the referendum, he said the land still has to be appraised. The city spokesperson didn’t have a ballpark regarding how much the property is worth. Porter and his team will also have to meet with the city to work out a purchasing agreement. It would be at least three years before the project is complete, Porter said.