Supreme Court weighs arguments in Florida-Georgia water battle

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. - The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday plunged back into a years-long water battle between Florida and Georgia, at times sounding skeptical of arguments that more water should be directed to Florida in a river system shared by the states.

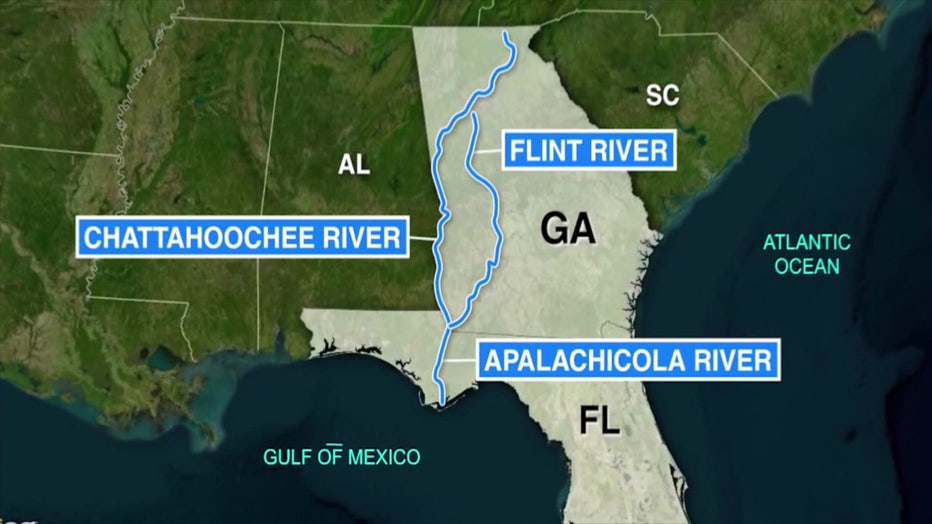

The fight is rooted in a collapse of the iconic oyster industry in Apalachicola Bay at the southern end of the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint river system, which starts in northern Georgia. Florida contends that Georgia farmers use too much water to irrigate crops, causing downstream damage to the Apalachicola River and the Franklin County bay.

But during an hour-long hearing Monday, justices pointed to conflicting evidence about whether Georgia’s water use is responsible for damage in the bay and questions about how to balance the interests of the states.

Chief Justice John Roberts asked Florida’s attorney, Gregory Garre, how the court should view the case if the record shows that "Georgia contributed to the collapse of the oyster harvest, but not enough to cause that on its own." Roberts suggested that "a lot of things took a stab at the fishery," including drought, overharvesting of oysters and Florida’s regulatory policies.

"But you can’t say that any one of those things is responsible for killing the fishery," Roberts said. "How should we analyze the case from that perspective?"

Justice Stephen Breyer and Justice Samuel Alito asked about conflicting evidence and conflicting reports by two special masters who were appointed by the Supreme Court to make recommendations about the case.

Featured

Ban on oyster harvesting is latest blow to Apalachicola Bay communities

The state’s oyster industry got some very bad news just before Christmas. Florida is banning oyster harvesting in north Florida’s Apalachicola Bay. It’s another blow for communities that have already gone through a lot.

Georgia has argued that the oyster industry sustained damage because of overharvesting after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster sent oil spreading through the Gulf of Mexico.

Breyer said to Garre that one big hurdle for Florida is testimony from experts "that there was overharvesting of the oysters, and that was the major cause. That’s your basic problem."

But Garre said water used in Georgia for irrigation has "skyrocketed," causing damage in Florida, including increased salinity of water in the bay. Garre said Florida is not arguing that water use in the metropolitan Atlanta area has caused the problems.

"Here you have overwhelming evidence of harm," Garre said. "You have overwhelming evidence of what’s causing that harm."

Craig Primis, an attorney for Georgia, contended that Florida has not proven that Georgia caused the problems in the bay and described overharvesting as a "self-inflicted wound."

"Florida failed to demonstrate that Georgia’s water use caused the oyster collapse," Primis said. "Instead, the record shows that Florida allowed oyster fishing at unprecedented levels in the years preceding the collapse."

Florida filed the lawsuit in 2013, though battles about water in the river system date to the 1990s. Florida is seeking what is known as an "equitable apportionment" of water, which could lead to new limits on water used by Georgia farmers.

Featured

Apalachicola Bay water sources dry up, but legal bills from court battle still flow

Florida and Georgia have been fighting over access to fresh water for decades. And now Florida fishermen are paying for it.

Monday’s hearing came after Special Master Paul Kelly, a New Mexico-based appellate judge, in December 2019 issued an 81-page report that said mismanagement by Florida contributed to the oyster industry’s collapse and that Florida had not adequately shown that Georgia’s water use caused problems in the bay and Apalachicola River.

Kelly was appointed special master after a divided Supreme Court overturned a 2017 recommendation by another special master, Ralph Lancaster, who said Florida had not proven its case "by clear and convincing evidence" that imposing a cap on Georgia’s water use would benefit the Apalachicola River.

Writing for a 5-4 majority in 2018, Breyer said Lancaster had "applied too strict a standard" in rejecting Florida’s claim.

During Monday’s hearing, Alito alluded to the complexity of the details involved in the case.

"This is about the most fact-bound case that we have heard in recent memory," Alito said to Garre. "And we have two comprehensive reports by two outstanding masters and they are not, to put the point perhaps mildly, not entirely consistent on a number of key points. What do we do with that?"

Breyer, at one point, asked whether the states had ever tried to settle the case --- though he acknowledged the question was "irrelevant."

"This has been going on for years, and Florida thinks that it wouldn’t cost Georgia much to remedy the situation," Breyer said. "Maybe Georgia has a different view. But has anybody ever tried to work out that Florida would pay something to Georgia to solve the problem?"

Featured

'It breaks my heart': Florida shuts down bay known nationally for its oysters

Because of a dwindling oyster population, FWC is shutting down oyster harvesting in Apalachicola Bay through the end of 2025.

Amid the court battle, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission in December suspended wild oyster harvesting in the bay as part of a $20 million restoration effort.

While Primis argued during Monday’s hearing that Florida’s request in the lawsuit would cause economic damage for Georgia farmers, Garre cited the importance of the oyster industry in the Apalachicola area.

"It’s hard to imagine New England without lobsters or, say, the Chesapeake without crabs, but in effect that’s the future that Apalachicola now faces when it comes to its oysters and other species," Garre said.